July 17 – 26, 2018

A dilapidated green Lada with a cow trailer and 1 cow in tow comes lumbering and creaking down the dry and desolate road. The Lada is a ubiquitous Soviet era economy car from the 70’s and 80’s. If people think old Volvo’s are boxy and unstylish, they have never seen a Lada. They effectively are a box on 4 wheels and in this former Soviet region, they are everywhere. They are built like tanks and ultra reliable yet as a result of the Cold War, were never exported. This one is dented, faded, rusted, with a cracked windshield, missing all four hub caps, 1 head light, and part of the front grill. It looks like I feel – and perhaps how I look. It lurches and chugs over this shabby road, much the way I have been the past 4 days. A man in his 50s climbs out and shakes mine and Ivo’s hands. The 2 engage in what seems like a very detailed conversation in Russian, even though Ivo at best speaks only a few words in Russian. Moments later, Ivo informs me that there is a path over the mountain pass which would allow us to get off this road and spare us another 60 miles of cycling around the lake – effectively a short cut. But it is only for horses and it is very unlikely that we could drag our bikes over, especially in our weakened and battered state. Dejectedly, we push on. I put on my best happy face but that too is battered. In truth, I’m done. We have been cycling for 8 hours today and 6 hours the day prior, uphill, into a consistent and relentless 25 mph headwind on a road that vacillates between a decades old dried up river bed full of marbles and a corrugated, sand filled wash board. It’s not prohibitive. We’re pedaling, slowly. I feel like we’re making progress until I realize we’ve gone less than 60 miles in 2 full days of all out war. Why won’t this fucking wind stop?

We are making our way west, from Naryn to Baetov for a much needed rest. Even though we are in a valley, it sits at over 10,000 feet, nestled in the crease of a 14,000 foot mountain range. The sun is intense. I resort to wearing thermal arm warmers as that is the only thing I can do to keep the laser like UV rays from scorching my skin any more. The skin on my legs, however, is already gone. It is flaking off like chalk. It has been 5 days, and we are not only running out of energy, enthusiasm, and optimism, but also out of food. Water too has been difficult to find as many of the rivers are suffering the same effects that we are. I hate this and cannot fake it any longer. The way the wind can wear down and hollow out mountains over time, I too was being slowly worn down and hollowed out.

We have been above 10,000 feet for nearly 2 weeks and as a result have not seen many trees. That means when it rains, there’s no place to hide. When it is sunny and hot, there is no place to hide. When it is windy (and it is always windy), yes, you guessed it, there is no place to hide (except for the occasional abandoned military bunker buried ¾ of way in the ground).

Two days ago we were camping in what might be one of the most beautiful valleys I had ever seen. We had followed what was labeled as an “old 4×4 road” on the map. “I don’t think this is a road,” I chuckled back at Ivo as we heaved our bikes up the side of a mountain, still playful and exuberant. The road, like many of the buildings that we’ve passed by in this area, seemed to have been reclaimed by the land. The only remaining semblance of a track to follow was a series of knee high posts going straight up 1 hillside, down the back, and over 3 more similar spirit crushing passes – 3,000 vertical feet of pushing, spread over 15 miles. Remnants of old rusty barbed wire were strewn about, ready to wrap its way around our ankles and wheels. It appeared that it was likely not a road but rather an old border wall separating Kyrgyzstan and China. This would seem to explain the faint tank tracks paralleling the wall – which is not to overlook the underlying fact that there were still visible tank tracks, further confirming that not many people had been in this place the past few decades.

After 4 hours, we plunged down what could best be described as a mine shaft to the valley floor, heating up the brake rotors and skidding my back tire down the scree field of loose rocks. We once again fell upon the same lush green velvet carpet that was this time snaking its way along a gorging river in between 2 insidious spiked granite walls up to Kel-Suu lake. The river churned. Horses darted by. In my head, I’m thinking, “This may be the most peaceful and gorgeous valley I’ve ever been in.” Unfortunately, we discovered that the lake is feeling the affects of climate change. It is nestled in a bowl of granite spires just over the gates of a rocky saddle. Until the sun seeps over the tops of the peaks each morning and turns the lake bottom to a creamy peanut butter, it is but a frozen and cracked moonscape floor, dry and barren with barely any water in site. I now know why the swiftly moving waist deep river that was being sourced by this lake is a chocolaty brown gruel.

The next day, we continued rolling through this carpeted green steppe. The hills ripple and undulate like the comforter on an unmade bed. I hear sounds of sheep perched high up on the distant hillside, interrupted only by the frequent crossing of horses, darting across our path. To say that Kyrgyzstan is wide open and wild would be an understatement.

And yet, with all this physical beauty, I yearn for more interaction. The population density of Kyrgyzstan is significantly less than the United States, with a majority of the population concentrated in few areas. I can ride for days in this region without any other human connection – but this is really the antithesis of what drives my passion and curiosity of bike travel – the human experience. The interactions feed me, energize me, and allow me to see a world through a different lens, even if only briefly; that is maybe why I’m so broke down…that, and this fucking wind.

I was nearing my breaking point. We had finally gotten off the dirt road from hell, turned slightly, and no longer directly into the head wind. It was a much needed reprieve from the constant whirling and drumming in my ears. We were approaching the border check point of Torugart, separating China from Kyrgyzstan. Normally, border areas are the most shabby and ugliest part of each country. It really should be just the opposite. Almost like – “Welcome to our country! Here is what you have to look forward to!” Instead, these areas seemed to be in the most disrepair, the most overlooked, the most neglected. This was definitely the case here. We passed a closed down petrol station before encountering 3 Soviet era caravans lined up on the side of the road. Much like the Lada, they were dented and rusted boxes of weathered metal, showing the effects of years of harsh conditions and neglect. As we slowly pedaled by, an older man in his 50’s whistled at us to come over. He was stocky, wearing a winter cap, and in spite of his missing front teeth, he looked like a teddy bear. His smile and eyes displayed the warmth and kindness that I was needing at that moment. He invited us in to his caravan where his wife offered us all fried eggs and bread. We sat at their table, the walls lined with tattered yet decorative red tapestries, displaying a much more elaborate feel than the outside of the metal caravan would have us believe.

After refilling our stomachs, and also our emotions, we forged ahead, 2 more grueling days and 3 more spectacular passes before descending 5000 feet to the hot and dusty village of Baetov where we found the first guest house, appropriately labeled “Desperation Guest House” on our map. The building conjures up visions of classic Soviet era minimalistic architecture. It is a simple, 2 story concrete building, painted white with long, cold, echoing halls. Everything is in fact concrete. There is nothing unique to distinguish this from any other building in town, which seems to be the Soviet way. The rooms are private with twin beds, a shared shower, and 4 basic outdoor toilets – which really is just another concrete structure with dividing walls and holes cut in the concrete floor. The staff is friendly and warm and one of them speaks reasonable English. Right now, it is everything I need.

Finally, I have a time to reflect on my first 2 weeks in this unique land, which is very different than my own. I remember growing up a kid in the 80’s and wondering what this part of the world was like. I saw all the classic USA vs USSR movies like Rocky IV and Red Dawn, pitting the mighty Americans versus the diabolically cold and angry Soviets. We had a very constant stream of propaganda flowing into our minds through our news and movies. But I always wondered, what were the people really like? Did the entire country really hate us? Thus far, everyone whom I’ve met has shown me nothing but kindness. The language barrier is legitimate, but a warm smile and a friendly hand shake can convey so much with regards to their curiosity and interest in my journey.

Delving deeper, I too am curious to know, those who were alive before the fall of communism and those who have only known the after effects – how do they see the world? I’m sure their views are a stark contrast. People who are in their 40’s or older, who knew a life of communism, where most people had a similar lifestyle – were they happier than when they knew their most basic needs were provided? Is their life harder now or do they feel a sense of new opportunity and potential for upward mobility? In the west we talk about striving for a “better life”. In Kyrgyzstan, the people in small towns, the rural shepherds and small business owners – how has their life changed after communism? Do they yearn for this better life? What is a better life and how does each person define it? These are of course subjective and cultural inquiries that cannot be easily answered.

As Americans, we have no understanding of this complete paradigm shift from the lives of people in the former Soviet republic. And it doesn’t just pertain to the people in this region. I have experienced this in other countries that I have traveled to, leaving me with the same questions. We have everything and it’s so easy to get caught up in the pursuit of stuff, but does it bring us joy or just leave us wanting for more, never really being fulfilled? A bigger house, a newer car. Is that unique to Americans or does everyone have similar desires, but maybe on different scales? To me, it seems it’s like a sugary soda. It gives us an initial high, but when that wears off, we come crashing down, usually with a dull lethargic headache, waiting for the next fix – bringing me back again to the question then: What is a better life and why are we so compelled by this concept?

I’m totally depleted physically and emotionally, and thus my mind is wandering to these existential ponderings, yet I am conscious of the fact that this opportunity of traveling through Kyrgyzstan is a gift – to connect with people who I only saw through the clouded lenses of gross misrepresentations in movies and news media. The literal highs and lows of traveling in this boundless and fascinating country from 14,000 ft peaks to 10,000 ft valleys run a very close metaphorical parallel to my euphoric emotional peaks and conversely my completely decimated valleys. At the end of the day, I’m further reminded that wherever I go, people really are just people, trying to get by – and we all have our own peaks and valleys throughout life.

Waiting out a storm in an old bomb shelter

Endless passes to climb and descend

Descending another lonely pass

I don’t think this a road?

Canyons for days…

Descending a steep “mine shaft”

Cruising along the velvet up to Kel-Suu lake

On the way to Kel-Suu lake

Kel-Suu lake is just over that saddle

Kel-Suu “Lake” Dried up but vast. That speck to the right is me

Hiding out in another bomb shelter

Outside of the bomb shelter

Slogging…

A yurt camp outside of Kel-Suu lake where we stopped for food

Food at the yurt camp

Just outside of Kel-Suu lake

Kel-Suu lake

Houses and settlements that time has forgotten

An evening visitor to our camp

Ivo at the border between China and Kyrgyzstan,trying to figure out a new route

Much needed snack in a caravan

The teddy bear who invited us in for food near the border

Some of the local biker gang

Chinese border wall

More settlements that have got lost in time

Another cemetery

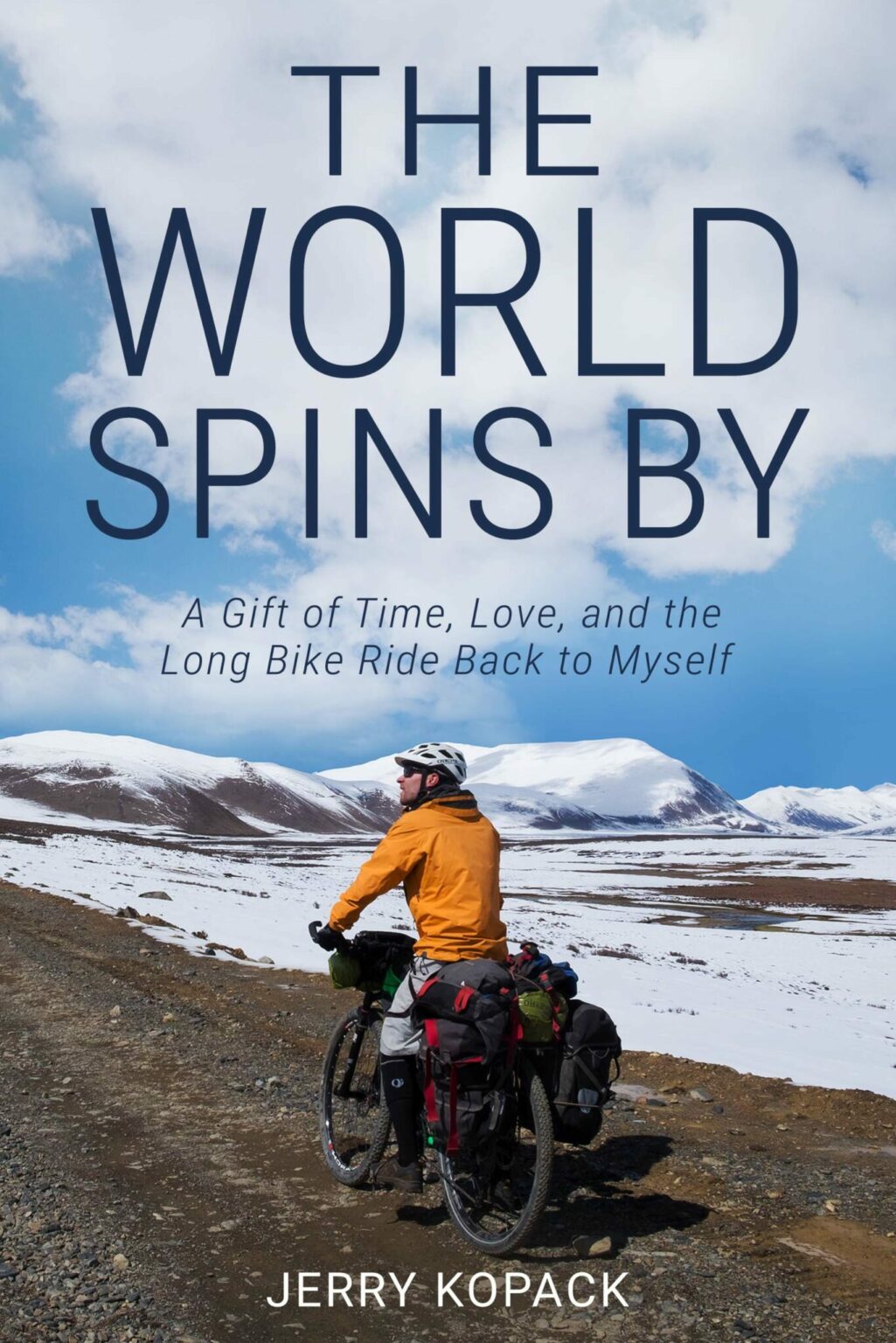

Lada

Running water is hard to find in Baetov and is trucked in. Apparently this kid is thirsty too

Once again, a beautifully written synopsis of your journey

Beautiful! So sad the lake is dry 🙁 I bet you were looking forward to jumping in it.